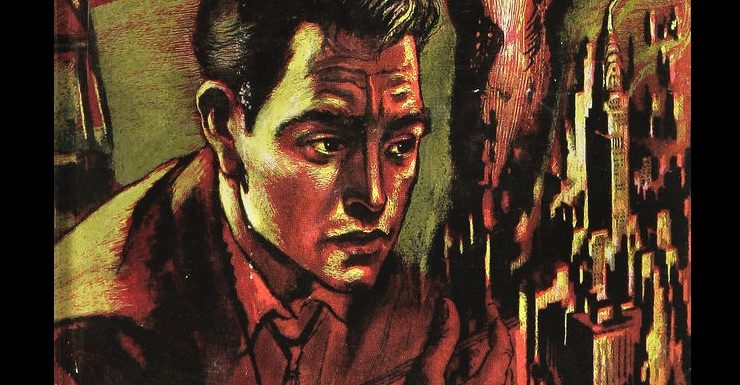

When the 1956 Hugo nominees were rediscovered, I realised I’d never read Leigh Brackett’s The Long Tomorrow. I’d read other Brackett and not been very impressed, and never picked this one up. But since it was a Hugo nominee, and since I trust the Hugo nominators to pick the best five books of the year, most of the time, and since it was the first fiction nominee by a woman, and easily and inexpensively available as an e-book, I grabbed it. And as soon as I started reading, it grabbed me. It’s great. I read it in one sitting this afternoon. I couldn’t put it down and it has given me plenty to think about. For a fifty-two-year-old book, what more can you ask? I still think the voters were right to give the award to Double Star, but I might have voted this ahead of The End of Eternity.

I don’t remember what Brackett I had read before—it was in my teenage ‘read everything’ phase. I remember it being pulpy planetary adventure, and I think it may have been a middle book in an ongoing series where I was supposed to be invested in the adventures of a character and wasn’t. The Long Tomorrow couldn’t be more different. It starts with a teenage kid being tempted to go to a forbidden prayer meeting by his slightly older cousin, and Len’s guilt and excitement and desire to know about the world is what propels this book. It’s not pulp adventure in any way. It may in fact be the first example of the American pastoral apocalypse.

Buy the Book

The Long Tomorrow

I’ve always thought of the American pastoral apocalypse as typified by Edgar Pangborn’s Davy (1964). The distinguishing features of the subgenre are that there’s been a nuclear war, it’s a few generations later, and the U.S. has reverted to a very Mark Twain-tinged nineteenth century. The hero—no inherent reason there couldn’t be a female protagonist, but I can’t think of any—is a teenager, and he grows up learning about his world, and the contrast between it and the lost civilization that is our world. There are fundamentalists who hate, loathe, and fear our lost civilization and all its works. And I think The Long Tomorrow is one of the very first examples of it, a founding cornerstone of the genre. John Wyndham’s The Chrysalids, is also 1955, so there’s no question of influence in either direction. A Canticle for Leibowitz, which doesn’t have a teenage hero but which is still somewhat in this space, is 1960. The Wild Shore is 1984, the most recent example I can think of.

In The Long Tomorrow, Mennonites and Amish have helped save the fleeing survivors of the cities, and got them back to a simpler way of life. Everyone is back on the farm. In a surreal piece of worldbuilding, despite all the cities having either been nuked or abandoned because they can’t survive without tech, the U.S.A. is still functioning to the extent that they have passed a “Thirtieth Amendment” to the constitution, and have federal law, though we only ever see it being enforced by angry mobs. The Thirtieth Amendment is that no town can have more than a thousand inhabitants or more than two hundred buildings in a square mile. This is to prevent cities arising ever again. But there are rumours that somewhere the evil Bartorstown still keeps the secrets that led to the destruction of the old world, the world Len’s grandmother remembers as a child, where she wore a red dress and ate chocolate rabbits. (Her son condemning the world that deserved to be destroyed for allowing the frivolity of a chocolate rabbit is a wonderful moment.)

The book is charmingly and compellingly written. It’s written in a very tight third person completely focused on Len and the way he grows up but won’t give in. This is a future than never was, but which must have seemed relatively plausible in 1955, when everyone was just starting to understand the nuclear threat—though in fact, from the evidence here they didn’t know the half of it. But I can see exactly why it must have appealed to the Hugo voters.

I’d never have guessed from internal evidence it was written by a woman. There are female characters. There’s the grandmother, who’s quite well done for somebody with so little page time. There’s the bad girl, Amity, and the good girl, Joan, neither of them more than a few quick pencilled clichés. All the male characters are better done—Amity’s father the judge has three dimensionality, as does his opponent. The girls barely exist to be plot tokens. This is a book about a boy becoming a man. It’s a very manly book. It was 1955. That was normal. In the same year we have Asimov with his clever villainess pretending to be dumb, and Heinlein with the devoted secretary Penny—but actually, both of them feel like more developed female characters than Brackett offers. It’s interesting to wonder why she made this choice—was it what she liked? Was it what she thought the audience liked?

It’s interesting to consider the tech here—when Brackett was writing, she was making the world revert about a hundred years, from 1955 to 1855. Reading it now, I realise how much easier that would have been than it would be to go from 2017 to 1917. The things the grandmother misses—TV, radio, bright dyes, chocolate rabbits, city lights—seem themselves relatively primitive to me. It was both easier for them to revert and would be easier for them to recover than it would be now. When the kids get hold of a radio, they can figure out how to operate it. Even apart from the issue of battery life, I don’t think the same would be true if people used to what they’re used to had something from today.

Now I want to talk about what happens, with spoilers, and especially for the end, so if you don’t want spoilers, stop reading now.

Unlike The Chrysalids—where the wonderful Sealand that is New Zealand retains technology and weapons, but we do not see up close whether it is actually such a great place when they get there after the end of the book—Len and his cousin Esau make it to the fabled Bartorstown. And there they find that everyone is living on the surface much as they do elsewhere, but underground they have both nuclear power and a giant computer. The giant computer is… I’m not sure if it’s sad or funny. It takes years to do calculations. Probably the ereader I was reading the book on has more processing power. But it was futuristic for 1955. It fills a whole room. And what they’re doing with these things that Len has been taught to believe are the devil’s tools, likely to provoke God to send another apocalypse, is not what I’d been imagining through the whole book. They’re not trying to restart civilization, they’re not trying to help the rest of America at all, despite having agents with radios everywhere. They’re trying to carry on the project they were put there for long ago, of creating a shield to guard against atomic bombs. They’ve no guarantee they’ll ever find one, even with the immense computer. They’re not aware that anyone has atomic bombs, or even atomic power except them.

When Bartorstown turns out not to be great, and especially when Len escapes from Bartorstown, I was delighted. I thought he was going to try to reintroduce civilization slowly. That, in my experience, is what people do in this kind of book. But no, the climax reconnects with that first prayer meeting, and hinges on whether Len will betray the man who saved him. Of course he doesn’t and he has to go back to the futility that he once imagined was salvation. That’s a very odd end! I found it deeply unsatisfactory. Were we supposed to think the quest would succeed—and if so, that it would be useful? The fear/faith he repudiates, great. And he says there are two attitudes of mind, the one that says here you must stop learning, and the one that says learn, and he’s for the latter. So far so good. But he’s doing nothing to further it by going back into what he has already recognised as futile. They’re all as bad as each other. I’d have preferred a little more hope in the ending.

But anyway, great read, an enduring good book, in print, and an excellent addition to the Hugo Nominees for 1956. I’m glad I read it, and I’ll be reading it again. And if anyone wants to recommend any other Brackett that’s this good or better, I’m eager to read them too.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published a collection of Tor.com pieces, three poetry collections and thirteen novels, including the Hugo and Nebula winning Among Others. Her most recent book is Thessaly. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here irregularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.